Note: This blog and these images were taken many years ago … but I saved it because I enjoyed the experience—I hope you do too 🙂

I am sure most of you have noticed that almost everybody who’s into nature photography has a special fondness for butterflies. We see them … we photograph them … and, to help identify which species is which, almost every one of us has a “butterfly field guide” or two that we keep handy. Yet the irony is, despite outnumbering butterflies nearly 14-1, there has never been the same level of interest shown in photographing moths as there has been interest shown in photographing butterflies, even though many species of moth are as ornate and colorful as any butterfly.

(Agrius cingulata)

Naturally, the primary reason for this lack of coverage/interest in moths is the fact most moths are active at night and we simply aren’t able to see them much. In fact, about the only time we do see moths is when they’re flying around the night light on our back porch. And let’s face it: photographing a moth (even a beautiful moth) on a screen door, a wall, or perched on a night light isn’t generally going to make for a great photograph (unlike a photographing a beautiful butterfly on a beautiful flower). The difference is in the background. Great nature photographs not only have great subjects, but they also have great backgrounds, and because moths are nocturnal, our opportunities to get a great photograph of a moth (with a great background) are simply going to be much more limited than our opportunities are of getting a great shot of a butterfly amidst a great background.

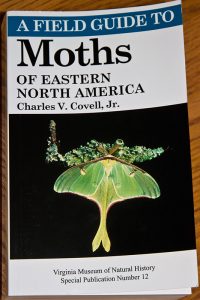

To make matters worse, there are hardly any books that have been published which are specifically devoted to identifying moths, so in many cases, even when we find a splendid little moth we really don’t know what to call it. In North America, for example, the first (and only) comprehensive, illustrated guide to studying moths was The Moth Book, by W.J. Holland, which was originally written in 1903 … and updated until the 60s … and this remained the ONLY guide for moths until 1984, when Dr. Charles V. Covell, Jr. came out with A Field Guide to Moths of Eastern North America. This book has since been updated in 2005, and (to the best of my knowledge) it remains the only comprehensive field guide to moths in North America to this date:

For any serious macrophotographer in Florida (or any of the eastern United States), A Field Guide to Moths of Eastern North America is a particularly good investment to assist you with the identification of any moth you may come across in the field, identifying over 1,300 different species. My only criticism of this book is the fact at least half of the photos are in black-and-white (I mean, hey, if you’re going to take the trouble to photograph the species to begin with, then have it be in color, folks!), but there are enough species shown in living color to make the book a worthwhile purchase … not to mention that Dr. Covell is considered the authority on moths in the Eastern U.S. (Dr. Covell is the Curator of Moths and leading research scientist at the McGuire Center for Lepidoptera and Biodiversity at the Florida Museum of Natural History, Gainseville, Florida … as well Professor Emeritus of Biology at the University of Lousiville, Kentucky.)

Unfortunately, not only are the photos lacing in superior quality, but in covering over 1,300 species, this still means that there are over 9,200 species not covered. Without superior photos to go by, many of which are black-and-white and of specimens not much more than 1mm in size, the book still is the best book southeastern macro shooters have to go by, although the moth section in Insects: Their Natural History and Diversity is an excellent resource also. Depending on your own geographical location, you may have a better book available to you than what has been mentioned, but probably not. Another possible solution to assisting you with identification would be to join an internet community devoted to species ID, such as BugGuide.net (for U.S. insects in general), or the Moth Photographers Group (for moths in particular). Naturally, you can also try requesting for help with a species ID here, and maybe one of the members will be able to assist you.

Moving on to the subject of photographing moths, you can try to photograph them at night, when you find them, and taking the time to get out there at night and photograph moths offers a unique challenge for macro photographers, but excellent results can be obtained if one is diligent enough in his efforts. You can buy a decent headlamp to go looking for moths at any Walmart sporting goods section, and although the ability to see and find moths at night is not as great as the ability to find and see butterflies by day, remembering the fact that moths do outnumber butterflies in kind and abundance by 14-1 ought to even your odds of success up a bit. If you’re lucky sometimes you can come up with some nice shots at or around your porch–or sometimes even on your finger:

(Diaphania hyalinata)

(Chloropteryx tepperaria)

Now while the above kinds of photographs can be rewarding, most of your night-time efforts are not going to bring you your best shots. Sure, the Emerald shot is interesting in a way, but it’s really not a nice photograph. To get really good moth photos, I find it is better to collect any moths you do find at night and keep them in a jar until the following morning before the sun comes out. Almost invariably when you photograph them in staged settings, illuminated by early morning light, your results will be far superior to just trying to ‘wing it’ photographing them at night as this Imperial Moth photograph demonstrates:

Staged Moth Photography

(Eacles imperialis)

(Actias luna)

(Paonias excaecatus)

(Trichoplusia ni)

(Utetheisa bella)

These moths were deliberately placed on plant items the following morning, after I had caught them the night before, which gave me much more control over both the composition as well as the lighting. I understand that some naturalists might be bothered with these methods, as some people believe that all ‘nature shots’ should be natural. Honestly, to an extent I agree, and if I were trying to call these ‘natural’ shots, then they should be shot in nature, as-is, but I am not. What I am trying to do is take the best possible shots I can of these moth specimens, and to do so I simply have to exercise some degree of control over the environment. You can be the judge here, but IMO these last 5 photographs show far better results than had I just tried to snap a shot of them on my back porch or with a headlamp on. Generally, I do try to photograph all life forms in-situ (as I found them), but some species’ life habits require that their imagery be staged in order to get the best possible results. (E.g., microscopic organisms, etc.)

I hope this article helps stimulate some ideas in you to use your macro gear on the moths that come into your own area daily. While photographing moths may not be mainstream, after you begin to realize just how many of them there are around you, every night on your back porch, you will soon realize that the potential for creative enjoyment is virtually limitless.

Enjoy,

Jack

(This was originally posted on my first Blog, back on October of 2010.)